All through the eighteenth century, Britain had profited from the slave trade more than any other nation. Finally, in 1807, an Act of Parliament was passed prohibiting the slave trade. The act also established a squadron of navy ships to patrol the West African coast and intercept slave traders of all nations, not just British traders. Between 1808 and 1860, the West Africa Squadron intercepted an estimated 1,600 ships and freed an estimated 150,000 slaves.

I had intended to come up on deck in time to watch the African coast disappear beneath the horizon, but I was detained in the sickbay. So I missed my chance to bid a formal goodbye to that brooding shore. Barring a halt for water and provisions at Tenerife, our next landfall will be Portsmouth dockyard, where I will receive my discharge from Her Majesty’s Navy, my back-pay, my bounty, and my prize money, and I’ll make my way home to Aberdeenshire. A ship’s surgeon no longer, I’ll use my earnings to set up a medical practice in the village square in Rhynie and be glad to spend my remaining days quietly among my own people.

Those eager lads who’ve read of the exploits of The West Africa Squadron in the

newspapers may wonder at my hatred of that green shore. In Aberdeen’s Footdee, gossiping among the drying nets and the crab pots, they’ll be thinking of the excitements of the chase as the slavers try to lose us in the velvet tropical night, the warning shots across the bows, the tight-lipped boarding party, service in a just cause, and all the panoply of heroism. And indeed, those eager lads have a point: the captain’s log shows that, in the last two years, our ship has captured no less than 21 slave ships and liberated 1,827 slaves.

But in the sickbay we see things a little differently. Lieutenant Anderson, the nineteen

year-old who had detained me in the sickbay, had once been an eager lad. Not so eager now, with blood in his stool, blood in his vomit, jaundiced and racked with muscular spasms – another victim of the Yellow Fever that afflicts us every time we drop anchor in Freetown. Nor is the Yellow Fever Sierra Leone’s only gift: no doubt there will be new cases of the Shivering Ague and the French Pox among the crew before we’ve buried the lieutenant.

I too was once an eager lad. I was born into a little timeless world, a world where my

father and his neighbours believed that trows – evil dwarfs – lived in hidden caves beneath Tap o’ Noth, the great hill that looms over Rhynie. Mr Alexander Gordon, our dominie at the village school, thought he saw promise in the crofter’s child, befriended me, and tutored me for the bursary examination in Aberdeen’s Kings College. When I walked the forty miles from Rhynie to the college in Aberdeen to sit the examination, I muttered over and again the liberty hymn of Robert Burns, til I came to those closing words, which I could not forbear to shout out-loud:

‘For a’ that, and a’ that,

It’s comin yet for a’ that,

That man to man, the warld o’er,

Shall brothers be for a’ that.’

Thanks to Mr Gordon’s instruction, I burned to play an honest part in the greater world.

And when I arrived in Aberdeen I smelt the tang of the sea for the first time: it seemed to me the smell of freedom. The lure of the sea never left me in my years at the college. So it was that, five years later in 1835, I signed up as a barber-surgeon in the West Africa Squadron, ready at last to play that honest part on those free seas. Then I encountered my first slave ship…

It was a Spanish brig, bound for Cuba, which we overhauled in the Bight of Benin. Once

the boarding party had made the decks secure, I went below to attend my new charges. The stench hit me like a punch to the face. My first encounter was with a woman holding a new-born baby: she had given birth while still shackled to a ripe corpse. In isolation, I believe I could have acquitted myself honourably with such a patient. But there were more than a hundred other slaves stacked in that fetid hold. I lurched round about and clambered, retching, back up on deck. Old Mr Morrison, our mate, seeing my distress, despatched below a group of the slave ship’s crew to free the slaves from their shackles and bring them up for treatment on deck. I have never ventured into a slaver’s hold since.

That was a hard lesson. The same Mr Morrison, a well-read man, later said to me: ‘Most

men are not of the wood of which saints and martyrs are carved.’ He meant it as a consolation and I took it as such, but over the years I have learnt a second, allied lesson by studying the Krumen.

The Krumen are the tribe of local fishermen from where we recruit replacements for our

dead and invalided ship’s crew. They are skilful seamen – deft and hardy – and fluent in the Pidgin English of the coastlands. I recruited one of them myself as an Assistant Surgeon: an older man, Joseph, whose quick intelligence and cheerful demeanour I had observed as I nursed him back to health after a bad fall from the rigging. He has proved invaluable in helping me treat our liberated slaves. I believe some slaves’ return to health is hampered by their initial bewilderment and inability to distinguish between an anti-slavery patrol and a slave ship. Joseph’s brisk kindness, as much as his communication gifts, serve to instil a belief in my patients that they are now truly released from captivity.

Joseph’s one fault, if fault it be, is shared by all the Krumen with whom I’ve sailed: it is a

refusal to have anything to do with the crews of the captured slave ships. I believe the antipathy is mutual, since a French slaver once told me that the slave-traders do not raid the villages of the Krumen, as they are thought to be too independent and turbulent to make useful slaves.

I first observed the trait in Joseph when an American slaver was brought to my sickbay

with an infected sore on his leg. The flesh was putrid: the patient’s only chance lay in

amputation, but the patient never recovered from the operation. I felt Joseph was partly to blame in neglecting the patient:

‘Damn it, man. Look at these dressings: how long since you changed them?’

‘Not changed, sir.’

‘He’s soiled his cot. Did you not notice?’

‘Not noticed, sir.’

‘Why, Joseph? Why have you left this man to die?’ I was exasperated, but in Joseph’s

answer lay my second lesson:

‘Sir, Krumen say this: good to wash away our sweat; bad to bathe with crocodiles.’

My sister has written that Mr Gordon has now gone to his rest in Rhynie’s kirkyard. When I return and pay my respects at his graveside, I shall tell him that there’s no harm in sharing Robbie Burns’s dream of a future brother-and-sisterhood of human kind. But I’ve learned that, in the ragged and gory present day, despite our good intentions, most of us should tread warily because very few of us have an infinite capacity to confront evil.

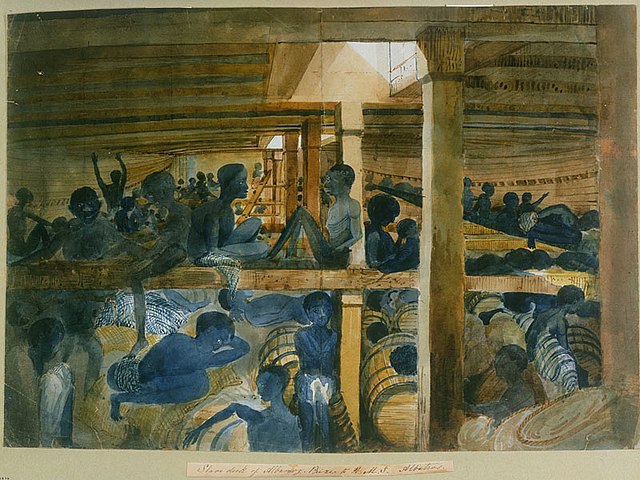

Image: – Wikicommons. This image is from a sketchbook of watercolours depicting places visited by Francis Meynell while on a Royal Navy anti-slavery patrol off the west coast of Africa and includes several ship portraits. This is one of two watercolours, the other being MEY/2.1, which show slaves above and below deck. They were painted on board the ‘Albanoz’, a captured Spanish slave ship in 1846, so the people shown had in fact been liberated though not yet landed and released. They nevertheless provide a rare eyewitness view of conditions in the hold of a slave ship. Those shown are not chained – and there are no signs of chains- but rather imprisoned in a confined space. During the Middle Passage, the enslaved were usually not kept constantly below deck, unless the weather was particularly bad or there was a serious threat of revolt on board. In order that as many Africans should reach the Americas with some of their health intact, they were allowed out of the fetid holds and to exercise on deck.

Fascinating piece of writing and handled without any mawkishness which makes it all the more effective. Clearly you have a very strong command of knowledge on this particular part of history which also makes the piece have authority and a good level of objectivity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paul. To be truthful, I’m not a historian, but around twenty years ago I arrived in South London too early for a work meeting and killed time by visiting the National Maritime Museum. I found there an exhibition about the West Africa Squadron and was fascinated, not least because I’d sailed with Krumen in the past (they continued to crew British ships). I’m glad to have been able to share my fascination.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Michael

Once again your skill with language and choice of subject are a perfect match. Slavery is evil (sad to still place it in present), we all know that, but stripping away the years that antiquate sin (in this case) is a fine skill; one you display on a regular basis.

Leila

LikeLike

Thanks Leila and thanks to the whole LS team for your past editorial suggestions to improve this piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Forgot to add that is a top notch image….

Leila

LikeLike

Yes, I was flabbergasted when I saw the header. Great to have the piece illustrated by a painting made by a member of the West Africa Squadron anti-slavery patrol! Thank you, Diane.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. I try to give the headers the thought that they deserve. I am happy that you liked it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A powerful piece of writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Steven, I always appreciate your comments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Mick,

This is one helluva heartbreaking subject. I take it this time in history is when the film (Sorry I am an un-read tit!) ‘Amastaad’ is based on – Belting film by the way – The ‘how they lightened the load’ scene is one of the most horrific and heartbreaking scenes I’ve ever watched!! That should be force-fed to our kids now-a-days.

Anyhow, the scene, where the MC went into the galley was brilliantly done. The authenticity, which you are probably the best at, is superb as it is so believable.

The Krumen’s humanity and conflict (??) was interesting and brilliantly portrayed. (I looked them up and as always, regarding the history, you are on point!)

This is one of those subjects that it is such a travesty that it STILL and always will need as much exposure as possible!!

I was delighted to see this published!!

From your stunning back catalogue, this is one of my favourites!!

All the very best my fine friend.

Hugh

LikeLike

Thanks Hugh. I’m sure other LS contributors will have thanked you for your enthusiasm, but like them, I really appreciate it.

I also need to confess that the mate, Mr Morrison’s, comment that ‘most men are not of the wood of which saints and martyrs were carved’ was lifted from GK Chesterton who, being dead, no longer needs it.

LikeLike

Effectively takes us to a horrible time and place. Closing line is

powerful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks David. Originally, the piece finished with Joseph’s line about sweat and crocodiles. Credit for the final paragraph should go to the LS editors for suggesting a more rounded ending. More proof that editors are always right.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Grim story, and the aftereffects still abound.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Doug. I think this is an occasion for using my favourite line for the second time on LS: Conceived in Sin, Born in Pain, a Life of Toil, and Inevitable Death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Intriguing story that could continue, could be many chapters in the life and adventures of the barber-surgeon. Ironic that he sea seemed to him to be “the smell of freedom,” and the first smell he mentions after that is the stench of the slave ship’s hold…

Dark times in history….. it’s amazing that Robbie Burns was so optimistic, considering the times in which he lived.

Indeed, bad to bathe with the crocodiles, as Joseph the Kruman says, soon the dead slaver’s body will be over the deck doing just that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re a close reader, Harrison: well-spotted re the contrasting smells. And I think you’ve come up with a fine alternative ending: just googled crocs and they do indeed swim in the ocean, albeit always close to shore.

LikeLiked by 1 person